“When at any time they cut off their enemies heads, they hang them about their horses necks…they fasten those they have killed over the doors of their houses…showing them to strangers…[but] they refuse to take for one of these heads its weight in gold”

– Diodorus of Sicily, 1st century BC

“Some of them use huge images of the gods, and fill their limbs, which are woven from wicker, with living people. When these images are set on fire the people inside are engulfed in flames and killed. They believe that the gods are more pleased by such punishment when it is inflicted upon those who are caught engaged in theft or robbery or other crimes; but if there is a lack of people of this kind, they will stoop even to punishing the guiltless.”

– Julius Caesar , 1st century BC

Around 387 BC, the Romans were defeated in battle by invaders from the north, who then marched on Rome itself. At last, when disease and famine had ravaged both the Romans and the invading army, they agreed to a truce. The invaders would only accept a thousand pounds of gold, but, according to the Roman historian Livy, the scales they brought to weigh the gold measured less gold than there actually was. When the Roman negotiator objected, the leader of the invaders threw his sword onto the pile of gold and cried: “Woe to the conquered!”

These descriptions are perhaps the most outrageous things the Romans said about a people they called Galli or ‘Gauls’, but who called themselves Celtae or ‘Celts’. In the 4th and 3rd centuries BC they poured out of their homeland in West Central Europe and terrorized the civilized peoples of Greece and Rome. Stereotypically tall, with fair skin and long light hair and sporting beards and moustaches, they were the archetypal barbarian that these peoples feared. They wielded long swords and rode in chariots when they had long since gone out of fashion everywhere else. They were quick-tempered and fond of boasting, always up for a fight and spoke in riddles.

They came from what is now France and Luxembourg, as well as neighboring parts of Belgium, Germany, Switzerland and also the nothern parts of Spain and Portugal. But we don’t tend to think of these lands as ‘Celtic’ today; instead you will hear of Scotland spoken of as a ‘Celtic nation’ alongside Ireland, Wales, Cornwall and Brittany. Why is this? These peoples never called themselves ‘Celts’ in their native tongues, nor did any of the Greek or Roman historians, so where’s the connection? When did we start calling the natives of the British Isles ‘Celts’?

In 1707, a Welsh linguist called Edward Lhuyd discovered that the native languages of the British Isles all belong to the same language family. Not only that, but the languages once spoken by the Ancient Celts on the Continent also belonged to this family. He decided to use the term ‘Celtic’ for the whole language family and term has stuck ever since.

Some have questioned whether it’s appropriate to call the Scots, Irish, Welsh, Cornish and Bretons ‘Celts’, because the label was given to them by a linguist based on the similarities between their languages and those of the Ancient Celts on the Continent. But this still begs the question: why were these languages so closely related to begin with? Did Celts invade the British Isles once upon a time, replacing whatever languages were spoken there before?

The Roman historian Tacitus, writing in the early 2nd century AD, thought that the Gauls must have taken over Britain because their language and culture were so similar. Archaeologists used to think they had proven him right, because they discovered two sites in the mid 19th century that could be linked to the Ancient Celts: ‘Hallstatt’ in Austria and ‘La Tène’ in Switzerland. Because the Greek historian Herodotus said that the Celts lived in the Alps, they believed they had found the Celtic homeland.

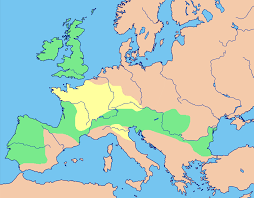

Hallstatt culture in purple, with earliest La Tène represented by stripes

Early La Tène (yellow) and its spread (green)

La Tène harness fitting

Since artefacts found at these sites were also being found in lands where Celtic languages were once spoken (including the British Isles), they reasoned that the Celts had spread out from the Alps and settled in those lands, bringing their languages and culture with them. Artefacts in the Hallstatt style are dated between 800-450 BC, while those from La Tène are dated from 450 BC onwards. So it was thought that this was when the Celts spread around Western Europe, during the Iron Age.

We now have genetic evidence to back this up, because a study from 2021 has found that genetic markers which were more common in Bronze Age France turned up in Britain in the Iron Age. But there is a twist to this tale: these genetic markers only turned up in what is now Southern and Eastern England, but not the rest of Britain1. Also, while the study didn’t cover Ireland, so far there’s no evidence from the ancient genetic record of Gaulish genes making their way to Ireland in the Iron Age either.

This means it’s unlikely that either the Picts in Scotland or the Gaels in Ireland owed their languages to Gaulish immigrants or invaders. It probably also means that the Hallstatt and La Tène artefacts found in these areas were traded for, rather than brought by immigrants. Over time, archaeologists also started to notice that Hallstatt and La Tène artefacts haven’t really been found in Spain or Portugal, both of which are places where folk that called themselves ‘Celts’ lived.

That would imply that Celtic languages were already spread across Western Europe by the beginning of the Iron Age c.800 BC. While the 2021 genetic study found evidence of folk from the Continent moving to Britain since 1500 BC during the Mid Bronze Age, they still weren’t moving as far north as Scotland (and they probably weren’t going to Ireland either). All of this means that there’s no proof that either the Picts or Gaels owed their languages to outsiders.

This then begs the question of why the Picts spoke such a similar language not only to the Britons, but also the Gauls, since their languages all belonged to the subgroup known as ‘P-Celtic’. Likewise, Gaelic languages are ‘Q-Celtic’ like the Iberian Celtic languages of Spain and Portugal, so does this support the idea that the Gaels descended from Iberians? We’ll probably never know the answers for sure, but genetics might help us understand exactly how all these groups were related to each other.

The last significant migration before 1500 BC was about a thousand years earlier, in 2500 BC at the end of the Stone Age. A study from 2017 shows that between c.2,700-2,500 BC, the Neolithic farmers of Western Europe were mostly replaced by migrants from the east known as the ‘Beaker Folk’.2 The Beaker Folk are named after their distinctive pottery shaped like beakers. They were closely related to the Corded Ware Folk, who seem to be where the Germanic, Slavic and other Indo-European cultures came from (including those in Iran and India).

Bell Beaker artefacts including bell beaker pots, copper or bronze knives, axeheads and razors, stone arrowheads and bone wristguards for archery

The first Indo-Europeans lived on the steppes of Russia and their descendants spread out in all directions. What is especially interesting about the Beaker Folk is that all Western Europeans today are descended from them, mainly through the male line. This means that the Romans and Gauls actually had a common origin among the Beaker Folk, but more importantly for this discussion, the Gauls had a common origin with the British and Irish.

After the Beaker Folk settled across Western Europe, they would have split into pockets that would have become isolated from the others because of geography, particularly mountain ranges like the Alps and the Pyrenees. In Italy, the descendants of the Beaker Folk gave birth to the Italic languages such as Latin (all other Italic languages were eventually replaced by Latin because of the Romans), while north of the Alps the Celtic languages developed.

The Celtic languages then split into the ‘P’ and ‘Q’ branches, because the ‘p’ sound in one is a ‘q’ in the other. An example of this is the word for ‘head’, which in Gaelic is ‘ceann’ (because ‘q’ turned into ‘c’) and in Welsh is ‘pen’. The fact that P-Celtic was spoken in Britain and most of the Continent outside Iberia probably means that the Britons and Gauls kept in contact with each other before the Gauls started to expand, including into Southern Britain. Linguists reckon Q-Celtic is the more conservative of the two, which probably means the Gaels and Iberian Celts became isolated from the other Celtic-speakers over time.

So if we come back to the question of ‘what is a Celt?’, we are left with a very interesting picture. Strictly speaking, the Celts were folk that lived in an area stretching from Portugal to Turkey in the Iron Age. But we now know that they shared a common origin with the folk in the British Isles, who spoke similar languages and had similar cultures. When a Frenchman feels the call from his Celtic past, he will look to the lore of the Irish and Welsh, because they preserved the Celtic myths (the Irish in particular) better than anyone else.

When you visit the parts of the Celtic nations where they still speak their native tongues, you will hear words rooted deep in the past of Western Europe. They seem not to be words from a tongue introduced by some Iron Age invaders, but those of languages that developed organically in the lands where they can still be heard. But even though the folk responsible for introducing them probably never called themselves ‘Celts’, why not call this common culture ‘Celtic’? Is there really any better label?

We know Scandinavians aren’t Germans, but we still call their language and culture ‘Germanic’ because they share a common root with them. It’s common that a label for one group will be used for other groups they’re closely related to, even if it’s not strictly accurate. The point is to emphasize the similarities, and we can surely show that all of the groups known in the past and present as ‘Celtic’ had a common genetic and cultural heritage that could stretch back thousands of years before the Romans ever wrote of ‘Celts’, ‘Britons’ or ‘Gauls’.

Conor Cummings