What the hillfort called the ‘White Caterthun’ in Angus might have looked like, by Kieran Baxter, pinterest.co.uk

Imagine you are living in Scotland in the year 218 BC, the same year Hannibal crossed the Alps to fight the Romans. You must see your tribal chieftain for an important matter; you have wound your way through the dark and dangerous paths of the Caledonian Forest, where you must beware of bears and boars. As the sun begins to set and mist falls upon the mountains, you see before you your destination: crowning a hill in the distance sits one of the many hillforts that dot the skyline. As night falls, you make your way up the hill and approach the gate.

The gate is made of wood and sits within a drystone wall with a wooden fence on top of it. Up on the top of the gate two guards stand, their spears looming up into the dark blue sky. “Halt!” one of them cries, “who goes there?”. You speak your business and you are granted entry, one of the guards comes down and opens the gate for you to enter. You walk along the path winding to the top of the hill, past roundhouses with smoke filtering through their roofs as you hear the sound of dogs barking and sheep and goats bleating.

Then you are greeted by the guards in front of the chieftain’s hall, speak your business once again, they allow you entry and pull open the door for you. As warm, dry air with the smell of roast beef wafts towards you, the chieftain beckons you to his table where he and his warriors are drinking and feasting: “greetings and welcome, kinsman”, he says. “Join us by the fire, what news have you from the north?”

You step inside and sit on a mat of skins. All around you are warriors tall and bold, dressed in linen tunics and woollen trousers and cloaks, chequered and colorful, red and yellow and brown, clasped with pins of bone. Most have long, braided hair and moustaches or beards, but some of the older ones that are balding have their hair cropped short.

Celts across Europe all had a similar culture and dress, they liked to wear colorful tartan, by Nachi, pinterest.com

You are offered a wooden tankard full of mead by your chieftain’s wife, whose dress is similar in pattern to the warrior’s cloaks and which is pinned with a bronze brooch that looks like a safety pin. The tankard’s handle is made of bronze and decorated with dots and circles. You thank her and take a sip, then pass it back to her and she smiles.

Bronze trinkets from Iron Age Scotland, the brooch is from the Castle Law hillfort in Abernethy in Perthshire and the tankard handle is from Carlingwak Loch in Galloway

You clear your throat and answer your kinsman: “The Wackomaggie are planning to attack this place on the new moon. I overheard one of them telling a member of an allied tribe, one of the Tikeselly, as I was travelling to a market. They want revenge for the killing of their chieftain in battle last month. I came as urgently as I could, what will you do?”

He and the warriors laugh and he unsheathes his shortsword, its handle made of bone and gilded with bronze. “Let them come!” he cries, “we will be ready to meet them. Thank you for this news kinsman, will you fetch your relatives and join me in defending my home?” You tremble a little, as you have never fought in a battle before, but you know how to fight. Every man must know how to fight in these times, for danger lurks around every corner and families need to rely on each other to survive and protect themselves and their livestock. But this is a chance for honor, to do great deeds and make your family proud. You gulp and say: “yes my chieftain, I will.”

He laughs again, “Splendid! I will send word out to more of my kin to come, now it will be our enemies that will be taken by surprise”. You sit with your chieftain and enjoy the feast, sharing less dramatic news about your cattle and how things are with your wife and baby son. The warriors tell you of battles they’ve fought and show you their scars, then once everyone is beginning to tire, the chieftain calls for his bard. He brings his lyre and sings the stories of the gods and of the victories of your tribe’s ancestors. With his last song he sings a tale of children turned into swans, softly as the warriors one by one fall asleep.

A statue of a bard with his lyre from Brittany, France, picture by Bernard de Go Mars

The next day you return home to call your relatives to fight. They are horrified by the news and most agree to help, though one cousin, Argentocoxos, is pessimistic about it. “I don’t see this going well for us” he says. “I think we will lose many men if we go, we may even lose the battle.” He has been right about things like this before, but you are undaunted and urge him to come. He agrees and a whole group of you, twenty men and one woman, head back to the chieftain’s fort.

It is now the day before the planned attack and everyone is spending their time training and preparing their weapons. The warriors keep drinking throughout the day. You join them but don’t have too much, since you need enough to calm your nerves but not too much to be sloppy. You take a nap as the beer begins to take hold of your senses, for you know not what hour the enemy will arrive and want to be rested enough to face them.

Suddenly, you are woken by one of the warriors: “It’s time” he says. You head out and the sun is setting, the breeze has a chill that makes you shiver, but somehow you feel determined and bold. You get dressed, taking a knife and several bone-tipped spears, one for thrusting and three for throwing, and your shield made of wood and covered in deerskin.

The Clonoura Shield from Ireland would have been typical for Iron Age shields, from the National Museum of ireland, Dublin (pinterest.com)

You emerge from the house you’re staying in, the stars are starting to peek out from behind the clouds as the sun sets in the distance. Your chieftain greets you: “are you feeling ready?” he says. “Yes, I am”, you reply. “You will do well” he says “I’ve seen you train, I think you’ve got a knack for throwing, give ’em Hell lad. Come, it’s time.” You walk up next to the wall and take your position. The plan is to wait until the enemy have climbed the wall into the fort, then take them by surprise.

The night draws on and it starts to get colder. You resist the urge to shiver for fear of making too much noise, but you wish for the enemy to come soon. Suddenly, at Toutatis knows what hour, footsteps can be heard on the grass outside the fort. A slight creaking can be heard as the ladders are hoisted up and make a slight tap as they land softly against the wall. You can now make out the faint outline of the top of the ladders. More creaking can be heard. Your heart begins to race as it draws closer.

You see a shadow leap up over the fence and onto the wall just above where you are. It’s too dark to see much, but the shadow runs off to the left to find the stairs. Once it finds them, it heads down into the yard and runs towards one of the houses. More shadows hop over the fence, along the wall and down into the yard. You reckon you’ve seen between twenty and thirty by now. Then, as more shadows keep coming over, your chieftain lets out a cry and the doors of all the houses are swung open, light and men stream out of them.

Then you see the enemy, bewildered and caught off-guard. You throw your spear straight at a man with long red hair and a moustache, dressed in a green cloak with red tartan. It pierces his leg and he shrieks in agony as he falls to the ground, as blood spurts out of the wound. One down, many more to go.

Iron Age British warriors, pinterest.com

Another rushes towards you, about to thrust his spear at your face. You duck, throw up your shield and manage to thrust your spear towards his chest. He parries with his shield and now you are in the dance of combat. Once more he thrusts at you, this time at your leg. You manage to jerk your leg to the left and stumble to the ground, but as he thrust down at you, you manage to quickly roll to one side as his spear pierces the ground. He lets go and pulls out a knife, but you see your chance and take it.

As he draws his knife, you thrust your spear at him once again, but he parries with his shield and laughs, then lunges at you with his knife. He manages to stab your shoulder, blood gushes out and you cry out and feel sick. You drop you spear, but your shield arm is still unharmed and you manage to parry another stab. Suddenly, as the man sees his chance and goes in for the kill, a spear pierces his throat. As he gurgles on his own blood, you look to your right and see Argentocoxos with eyes full of rage. As he draws his spear out of the man’s neck, he looks to you and smiles.

The enemy let out a cry of retreat, but your kinsmen have managed to get up onto the walls before they could and they are surrounded. They drop their weapons and hold up their hands, the battle is finished. The captured men are led away into the servants houses, where they will work until their tribe offers ransom for them.

One of the chieftain’s daughters tends to your wound, a pretty lass with small blue eyes and long, dark hair. The herbal balm smells wonderful, but stings to the bone and she manages to soothe your agony with softly-spoken words. Your chieftain comes in laughing: “You did well tonight lad, though if it weren’t for your kinsman, I daresay my daughter would be preparing you for your journey to Avalon now!”

You let out a strained chuckle and thank him for the opportunity to fight. You have killed your first man, you will now be able to return to your wife and tell her of your brave deeds and show her your scar. Your parents will be proud, you have defended your chieftain well. Who knows, maybe your son will be inspired by your story one day and will train to be a warrior. He might end up joining your chieftain’s service and wed a chieftain’s daughter, then your humble farmer family will rise in standing and have even greater honor.

If you find yourself on top of one of Scotland’s many windswept hills, you might see lumps and bumps in the grass or heather that were once ramparts. Sometimes, you might be surprised to see a stone wall, whether some is still standing or tumbled into a ring of rubble. If you happen to be there in the gloom of twilight and listen carefully, especially at a time like Halloween when the veil between worlds is thinner, you might still hear the ring of a hammer on an anvil, dogs barking or chickens clucking.

You might hear voices speaking to each other in a language that sounds vaguely like Welsh and, if you close your eyes, you might even see them walking to and fro in their linen tunics and woollen cloaks and trousers. You might see the roundhouses all about you and the walls as they once were, tall and topped with a wooden fence called a ‘palisade’.

Today we call these places ‘hillforts’ and once upon a time they were built all over Europe. From the name, you probably imagine something defensive, built to keep out invaders. Irish monks recorded hillforts in what is now Scotland being besieged in the 7th and 8th centuries AD during the Dark Ages. In those days kings lived in them, so they were basically like castles.

Sadly, the monks didn’t go into detail about how hillforts were attacked, but we can look to the native Maori of New Zealand for inspiration, because they built hillforts called ‘pa’. Sometimes it was just a case of starving out the folk inside it, but they could also be attacked by surprise at night when guards were less likely to be on duty1, which inspired the story I wrote above.

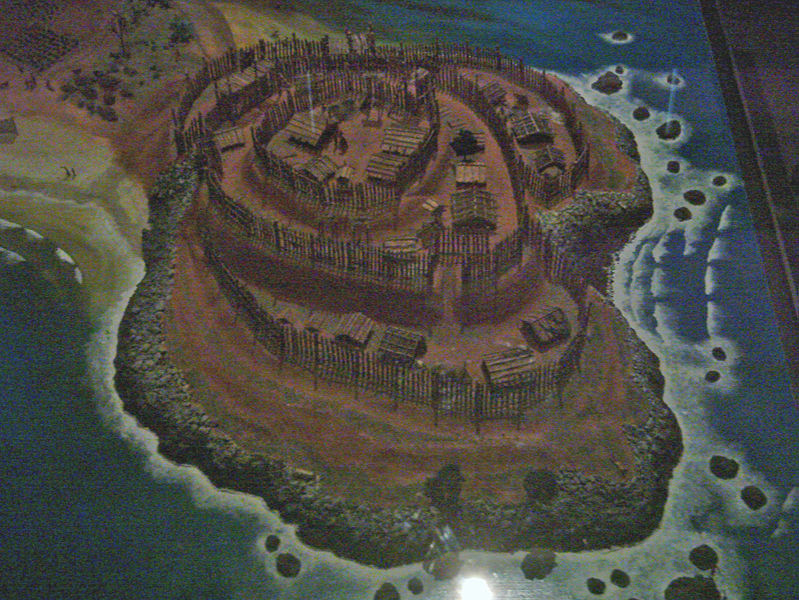

Model of a Maori pa, from the Auckland War Memorial Museum, New Zealand, by Ingolffson

But some hillforts just don’t seem like they would stand up to attack. The Brown Caterthun in Angus had many rows of palisades and the entrances through each were laid out in strange zig-zag patterns. There was also a spring in the middle of the fort, so archaeologists reckon it was more likely to be a pagan religious site.

So if they were built before Christianity arrived, how long ago was that exactly? It was long before there was a Scotland, since archaeologists have dated the oldest hillforts all the way back to 1000 BC, during the Late Bronze Age. Though it was so long ago that we have no written records to tell us why they were built, archaeology can give us clues.

It tells us that Late Bronze Age Scotland was run by an upper class of warrior nobles, who fought each other and controlled the production and trade of bronze. Everyone else depended on them to get bronze for their tools and weapons. They became so wealthy and powerful that they felt they had more in common with nobles in other parts of Europe than with the peasants who relied on them.2

We don’t know if they were led by kings or not, but they could have been. The Roman historian, Tacitus, actually wrote that “at one time they [e Britons] owed obedience to kings; now they are divided into factions and groups under tribal leaders.”3 Did the Britons who lived in the 2nd century AD when Tacitus wrote actually remember what things were like a thousand years before the Romans came?

There aren’t many Late Bronze Age hillforts, which probably means whoever lived in them ruled over large areas. Two of the oldest hillforts were built on Traprain Law in Lothian and Eildon Hill North in the Borders. Were they the homes of Bronze Age kings, each ruling over the areas that are now Lothian and the Borders?

The Late Bronze Age fort at Eildon Hill North was built on the very top of the hill on the right-hand side, but the more obvious ramparts were built a thousand years later. canmore.org.uk

But the appearance of iron around 800 BC would threaten this system, because it meant that the common folk could make tools without relying on the nobles. About 50 years later, the climate quickly became much colder and wetter4. Bronze was still traded and made into jewellery and swords, but the centralized system that managed it collapsed. Society reverted to tribalism and new hillforts started popping up everywhere, while old ones like Eildon Hill North were abandoned.

Did society descend into chaos now that the nobles no longer had control? Probably, because if there was nobody to enforce the law over a wide area, local tribes could raid each other and get away with it. Folk would have relied on their relatives for protection, so society in Iron Age Scotland would have worked a lot like the medieval clan system.

So who lived in hillforts now? Most of them were probably the homes of tribal chiefs, but as I mentioned above, it looks like some were probably places of worship where no one would have actually lived. Others could have been places of refuge for local communities if their villages were attacked.

At Turin Hill in Angus, a fort was built that was much bigger than the Bronze Age ones, so it could have been where the folk living in an undefended village below the hill could flee to if they were attacked. But later on, a smaller hillfort with a massive stone wall was built inside the bigger one. Since not as many folk could be fit inside of it, it was probably the home of a local chieftain.

The massive stone wall around that fort and others like it in North-East Scotland were probably built to protect the chieftain and his family, but they could also have been built to show off his power and greatness. It might not just have been about his ego though, since in many tribal societies, the power of the chieftain reflects on the tribe as a whole, so it was probably considered important to show who was boss.

But over time, more and more hillforts were actually abandoned, while old Bronze Age ones like Eildon Hill North were occupied again by the time the Romans arrived in the 80s AD. The new hillfort at Eildon Hill North was bigger than the old one, but it doesn’t seem like it was somewhere a community could flee to if they were attacked. Instead, it was more like a town, because lots of trade goods have been found there; including things brought by the Romans, who built their own fort not far from Eildon Hill.

The Romans liked to built their forts next to rivers so they could ship in the things they needed, u3ahadranswall.co.uk

What the Roman fort at Newstead might have looked like, they called it ‘Trimontium’, meaning ‘three hills’ because Eildon Hill has three peaks, trimontium.co.uk

The Romans said Eildon Hill North was the capital of a tribe called the Selgovae, so it looks as if many local tribes had merged into a bigger tribe that was starting to look more like a kingdom. Were the Britons becoming more peaceful as the climate warmed and the population grew? While they were still Celts and would still have been up for a scrap, things might not have been as cutthroat as they were back at the beginning of the Iron Age.

A more peaceful and stable society would have made it easier to trade, and we start to see this as bronze became more common again as the Iron Age wore on. If local chieftains wanted to flaunt their power, they probably didn’t need to live in hillforts anymore, but they could do it with bronze jewellery; not just their own, but also bits for their horses’ harnesses.

The brooch from Traprain Law is called ‘dragonesque style’ and it was imported from the Roman parts of Britain to the south. The bottom item is a pony cap, it would have originally had a plume on top. National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh

But after the Romans left Britain in 410 AD, Eildon Hill North was abandoned again and new hillforts were built. Once again, the climate was getting colder and trade connections with Europe were collapsing as the Roman Empire fell, so there’s a pattern there. Society seems to have become more violent again, but it also doesn’t look like it collapsed in Scotland the way it had at the end of the Bronze Age.

Instead, a new nobility arose, but society was still in-between the tribal and medieval stages; it was now the ‘Dark Ages’ or ‘Early Middle Ages’. This was the age of Arthur and of the Picts and Anglo-Saxons. Christianity had arrived, but society still worked the way it had for hundreds of years before. Druids would no longer make blood sacrifices to the pagan gods, but raiding was still how men would win honor and glory. The difference is that now we can actually match hillforts with the historical record, unlike in the Iron Age.

So when we visit hillforts like Dunadd in Argyll or Dundurn in Perthshire, we know they were besieged in 683 AD because the Irish monks told us so. But there is still so much that happened at hillforts that wasn’t written down; it’s called the ‘Dark Ages’ for a reason. So we still need to use our imagination to come up with stories like the one I wrote above if we want to immerse ourselves in the times when hillforts were built.

Still, we know enough to say for sure that kings lived in hillforts in those days, because at Dunadd there is a footprint cut into the rock where kings would place their foot when they were crowned. The monks tell us that a king ruled from Alt Clut, the fort where Dumbarton Castle now stands. That fort was besieged and taken by Vikings in 871, so it was abandoned and its kings moved to Govan instead, because it can’t be so easily reached from the coast.

The rock-cut footprint at Dunadd, the seat of Scottish kings before they took over Pictland

The Picts also decided to abandon their fort on the coast at Burghead in Moray because it was too vulnerable to the Vikings. The Pictish kings decided they wanted to live in a palace at Forteviot in Perthshire instead of a hillfort, but they probably fled to a hillfort if raiders came. So the days of the hillforts were numbered, because they reflected the tribal times and society was changing to become less tribal and more hierarchical and ruled by royalty.

The fort at Burghead is at the front, but the modern village has been built over the ramparts at the back

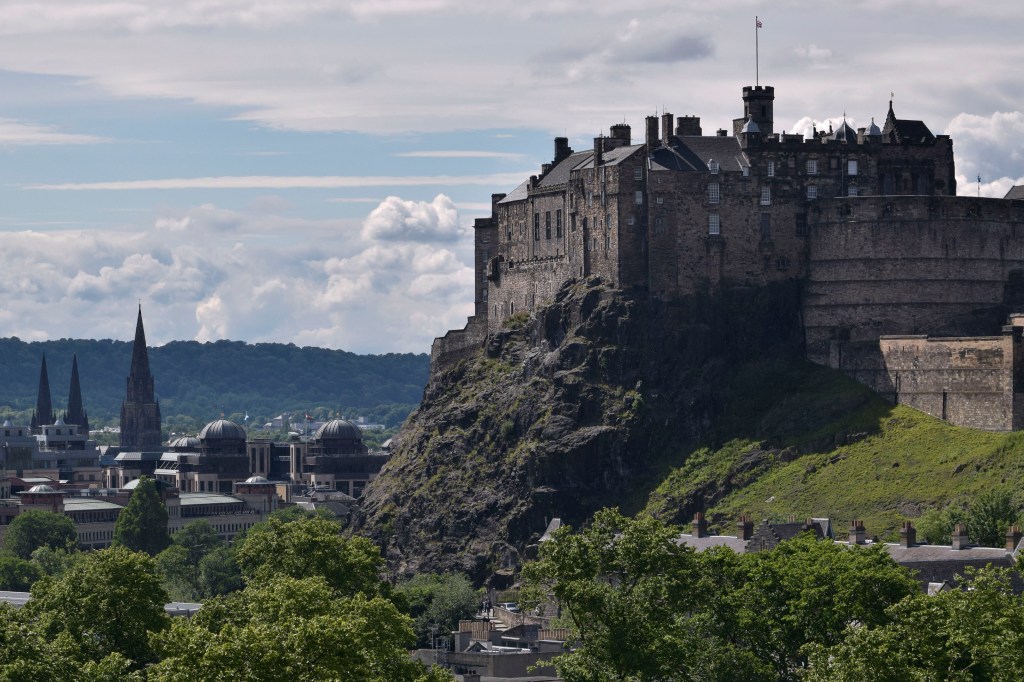

By the year 1000, all of what is now Scotland except for the south-west and the Isles were ruled by one king, so the days of tribalism were finally over. The hillforts were either abandoned or castles were built on them, like at Edinburgh Castle or Stirling Castle. But Scotland was still more tribal than England, because the clan system was based on descent from a common ancestor like the tribes of old.

The hillfort where Edinburgh Castle now stands was besieged in 638 by Anglo-Saxons

So that’s the story of hillforts, when they were built and why. At first they might have been built as the castles of Late Bronze Age kings, though we don’t know enough about that time to say for sure. But for the most part they were built when Scotland was tribal, when folk were focused first and foremost on their local communities, simply because the international system broke down and they had to rely on their kin to survive.

I think the days of the hillforts deserve more attention, because they can help us to appreciate what we have now. Folk were so much poorer and had to make do with a lot less than they had even in the Bronze Age, never mind nowadays. They left very little behind because they had very little. Instead, they were rich in traditions of the spoken word and had a much closer relationship to the land, even if it wasn’t out of choice, but necessity.

But they were also the days when the Celtic myths were crafted, so they can inspire us to learn more about our pre-Christian past and the roots of so much of our modern day fantasy. I hope that if you visit a hillfort someday soon, you’ll feel inspired to imagine what things were like back then, when folk valued courage and honor above all else. When warriors sat on animal skins and feasted in the splendor of victory or somberly in defeat, and when herblore and magic were needed in the face of disease or disaster.

Conor Cummings

- Chris Pugsley, NZ Defence Quarterly ↩︎

- Armit, 2016: Celtic Scotland, p.99 ↩︎

- Tacitus, Agricola, 12 ↩︎

- https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1408028111 ↩︎